Brice has spent the better part of his life in Los Angeles, with only intermittent absences, since his mother, the celebrated comedienne Fanny Brice, decided to move here from New York in 1937, when the artist was sixteen. During the late 1930s Brice decided to study painting full time, and he returned to New York to work at the Art Students League. Back in Los Angeles he resumed his studies at the Chouinard Art Institute and later joined Rico Lebrun and Howard Warshaw on the faculty of the Jepson Art Institute. A bond was created among the three artists due, in part, to their shared belief in the fundamental importance of drawing, something also stressed by the curriculum of the Jepson school. By 1953 Brice was invited to teach at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he continues to serve on the faculty.

Throughout his mature career Brice has always studied and reacted to the terrain of Southern California as illuminated by the intense white light characteristic of this area.

“In the fifties I was working on land and sea images. I used to go to the top of Mulholland Ridge and work directly from nature. At that time it wasn’t populated, and it was not uncommon to find fossils. The terrain was mountainous, a great dinosaur spine spilling into the sea, primordial and tenacious. The bushes cantilevered from the side of the hill with the ground eroding, the roots grasping and holding on; all of that fascinated me”

(from Brice interview, Diamond and Lewallen, pp. 10-11)

This strong sense of place, of identity with a specific ambience, is one of the persistent qualities in Brice’s art, a characteristic that serves to distance his achievements from the various national or international movements that emerged during the same period. The particularities of Southern California have helped determine Brice’s visual vocabulary in much the same way that the work of his friend Richard Diebenkorn radiates a sense of being rooted in a specific locale, no matter how abstract the composition.

Although Brice’s art reflects the specifics of a particular environment, the viewer’s options are not necessarily limited by this circumstance.

“One never knows what the viewer will experience, and one wouldn’t expect it to be the same experience as one’s own. Particularly in the context of association, there’s an enormous variety of possible responses, because everyone brings to the work the context of their own experience.”

(from Brice interview, Diamond and Lewallen, pp.6-7).

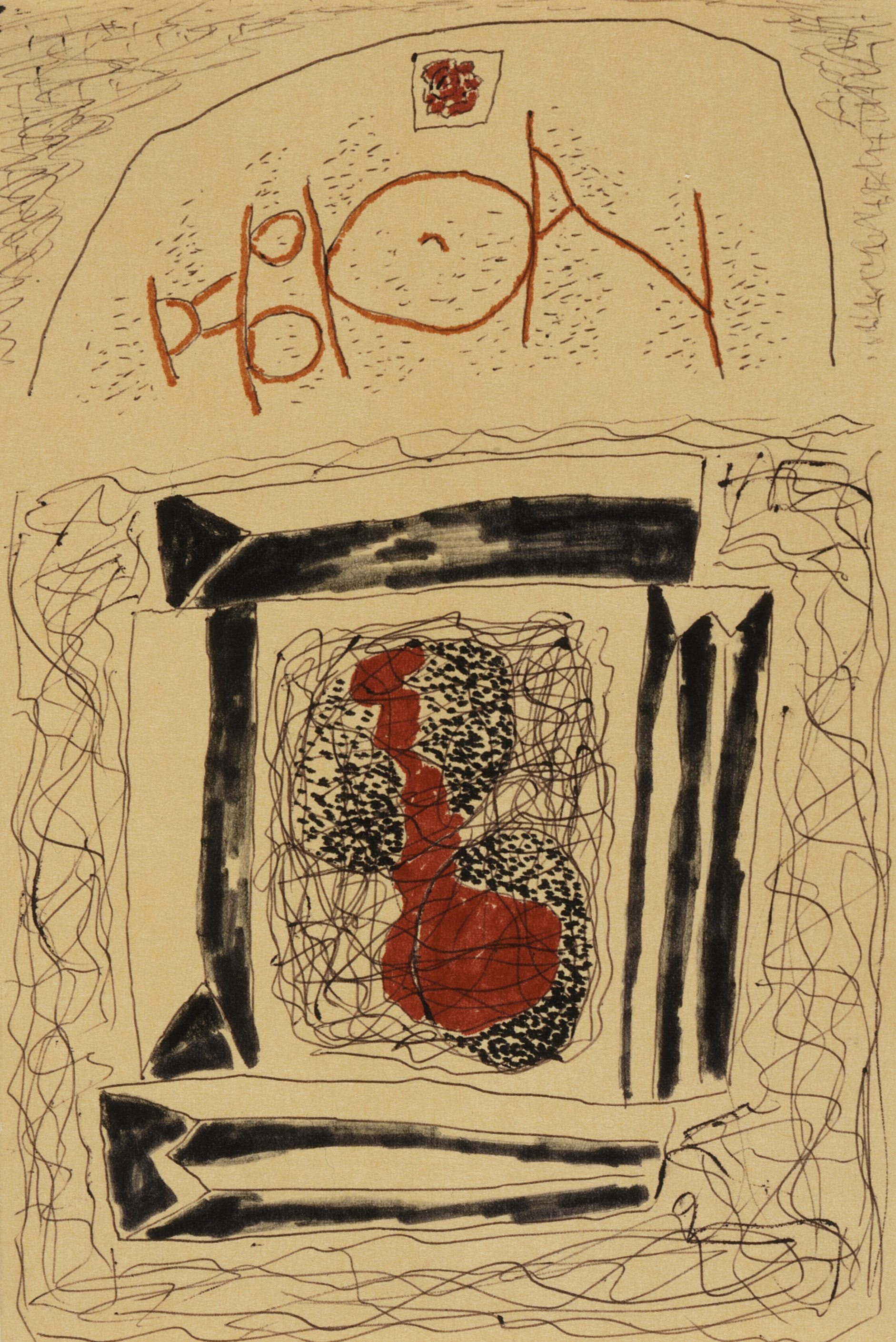

The Notations drawings offer an intimate view of Brice’s process and are engrossing for the multiplicity of associations they suggest. Fortunately the forty-eight drawings were acquired by a private collector, thus assuring that they will be kept together. The collector has agreed to make a future donation of the drawings to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a generous gesture that will preserve the unity of Notations and eventually add to our permanent collection a major body of work by William Brice.

Victor Carlson

Senior Curator, Prints and Drawings, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art