Part I (Interview by Wendy Diamond, December 1985)

WD: Bill, I’ve been reviewing some records of your work since about 1948 and have been struck by the remarkable consistency in your approach to painting. I’m curious to learn how you first conceived yourself as an artist.

WD: I thought I could start right at the beginning and ask you how a painting starts for you, where does it come from?

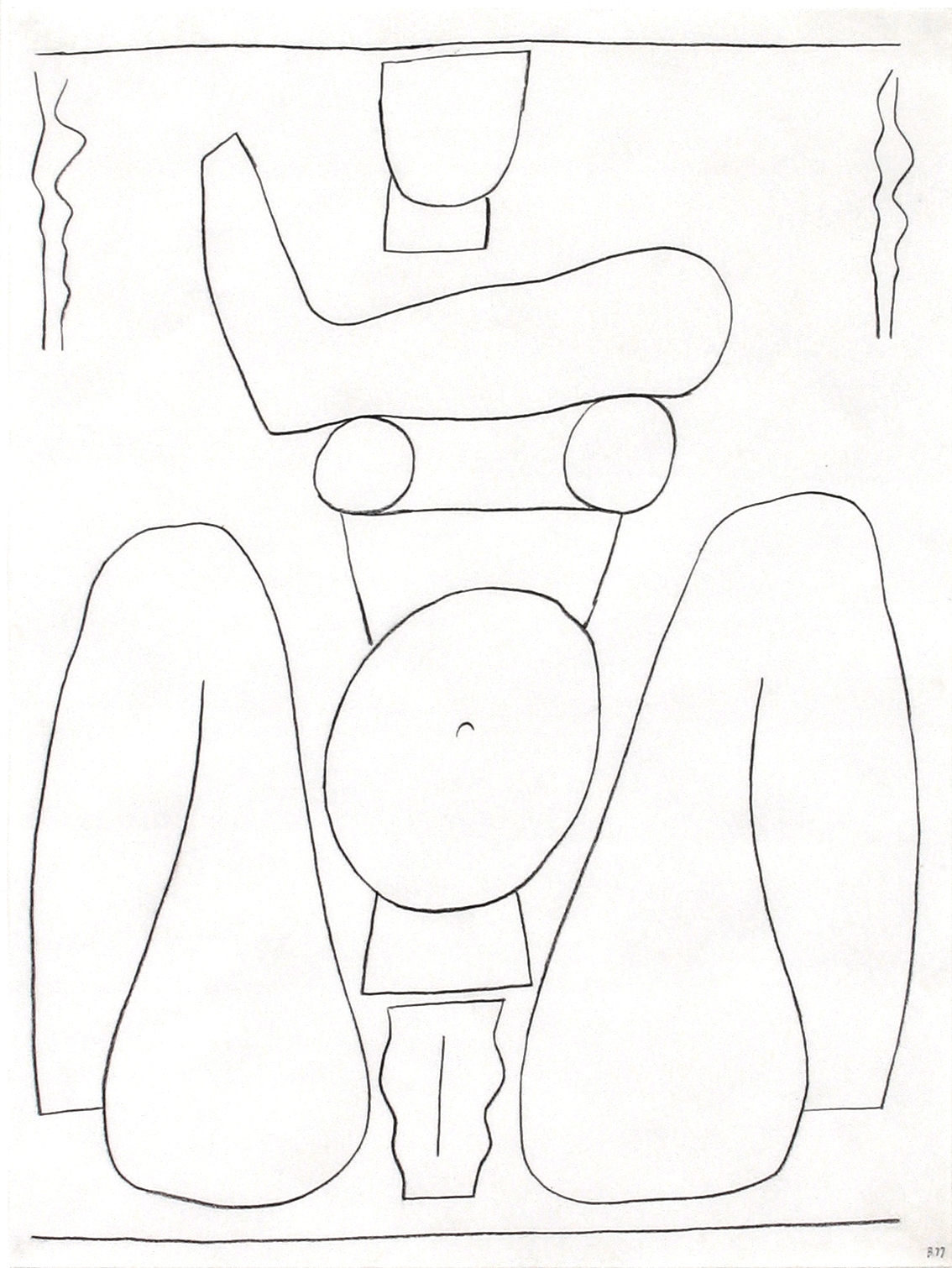

WB: Drawing is a continuous activity for me. Increasingly I feel that I want to act upon any idea or image that passes through my mind. I want to grasp it, to mark it. I also find that one drawing begets another, and the idea develops. I rarely use a drawing as a direct study for a painting. The drawings have a life of their own.

WB: They establish a vocabulary that I develop in painting. So the drawings and the paintings coexist. They are interactive. I think, because of the simplicity of the medium, the process, the drawings are of a different nature from the paintings. One of the fascinations of drawing is that all one needs is something with which to make a mark. It’s the absence of paraphernalia. It’s significant that some of the most moving works are achieved in drawing. Whereas drawing has always been a point of departure, in oil painting I will develop the emergent images and will work on a number of paintings at one time. Therefore, there’s a tendency for one canvas to inform another.

WD: Do you think of drawing as a separate medium from painting?

WB: I don’t think of it as separate.

WD: They interact?

WD: But one is more direct and spontaneous.

WB: For me that is definitely so, and there are issues that come along with that. On occasion, there are drawings that one works over a long period. But throughout the history of art, drawing has had a sense of immediacy about it—and directness. Partly that has to do with the fact that the extension of time isn’t the same. When artists work over an extended period of time, the painting has to include the differences of feeling, of day-to-day changes, and artists have to respond to those changes or incorporate or assimilate them without losing their way, so to speak. There are some artists who work so spontaneously and directly in painting that one could say it is akin to the time sequence of drawing. But sometimes I put a painting up on the wall for three months, and don’t touch it, and then pick it up again.

WD: You said you work on more than one painting at a time?

WB: Oh, seven, eight, and usually over a long period. In actual painting activity, I may work quite rapidly, but I change a lot in the work, so that often I work on a painting for a year and a half or two years.

WD: How do you know when a painting is finished?

WB: When there’s nothing more to be done. It’s like arriving at a destination; I might not know the location of the destination when I start out, but I do recognize it when I arrive.

WD: And that takes time.

WB: And that takes time. I’ve come to realize that. At an earlier time, I believed that there was a single destination, an idea of perfecting toward a result. There was a period in the early seventies when my work was changing, and I felt that I needed secluded time, a time to leave works open and incomplete, in order to experience the implications of the process itself in its various phases. That period extended into a number of years during which I began to recognize that for me there is, usually, more than one alternative and that the variations can be equally satisfying.

WD: Was that the period when you changed from the figurative work of the sixties to what you are doing now?

WB: Yes, essentially. I think the painting of the figure in the landscape of 1966 has some indication of the change. I am quite certain that the central tree form in that painting derives from the everyday experience of seeing the citron eucalyptus trees on our property, which differ from most trees. Usually, one can immediately see the growth pattern of a tree, and see that a certain amount of ground belongs to a tree because the root system has somehow altered the ground surface. Our trees are curious in that they’re more like telephone poles. Instead of looking like they are growing out of the ground, they appear to have been set down, because there isn’t any indication of their root system at their base. And they are rather tall and flexible. In a slight wind, you can put your hand on the trunk and feel the entire tree vibrating. I think that this is one of those instances when the physical environment influenced me, even unconsciously. In the paintings the trees became branchless, just trunks, and the intervals between these “tree columns” became increasingly significant.