Ocean and Rocks, 1954–55

oil on board, 64 x 80 in.

Collection of the San Diego Museum of Art

Gift of Mary Grant Price and Vincent Price, Jr.

To the extent that these Rock Compositions deal with subjects in nature, they have some slight affinity with landscape painting, and for a time in the early 1950s, Brice took an interest in painting the environs of Los Angeles, which then were considerably less developed than today. Big homes and gated communities now roost on what still counted as wilderness—though a somewhat citified wilderness—just a few decades earlier. Brice’s landscapes, as well as a related body of flower paintings, executed at the same time as the ascent of abstract expressionism, are among the most abstract works he ever made. Despite his remoteness from New York (where he did journey with some frequency), Brice was not unsusceptible to the compelling ideas and challenges of abstract expressionism that were invigorating American and international artists.

Land Fracture, 1954–55

oil and sand on masonite, 96 x 72 in.

Collection of the University of California, Los Angeles,

Hammer Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ray Stark

Yet even in his most inflected and abstracted works, strong suggestions of representational elements abide. Thus in a work like, say, Land Fracture (1954–55) in the collection of the University of California, Los Angeles, Hammer Museum, whose tortured painterly forms defy easy representational identification, there are clear aspects of landscape painting: a chunky rock-like formation, the branch of a tree, patches of blue sky and white clouds. Similarly, Mottled Things (1954) in the collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, verges on illegibility as a depiction, yet there are clear references to rock formations and other mottled things, as the title indicates. Brice’s impulse to abstraction is always grounded in representation, much as were some of the more radical experiments of early cubism: Picasso’s The Architect’s Table (1912) in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, for example, whose extreme faceting verges on nearly “illegible” visual display for its own formal sake, is nonetheless recognizably and resolutely a traditional still-life—albeit one rendered in a revolutionary visual vocabulary.

Mottled Things, 1954

oil on texture board, 55 7/8 x 18 in.

Collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art

In an interview for View, an irregularly published journal based in San Francisco, Brice commented that “I’ve never had an inclination towards descriptive illusionism, per se, toward the literal recording of perceptual appearance. Nor have I ever been a nonobjective painter,”3 preferring to root his art in stylized pictorial representation. Though there were many major mid-century modernists who emphatically combined robust abstraction with representational painting (such as Willem de Kooning with his fiercely painted women, or Arshile Gorky with his dream-like, surrealist-inflected imagery), in the main, they were primarily abstractionists who used recognizable images as a foundation upon which to “push paint”—to create gestural paintings and handle the medium of oil paint in a physical, at times acrobatic, display of passionate control over dynamic energy. Brice by contrast—himself a true sophisticate of painterly technique and of draftsmanship—seems always more compelled by pictures and our ache to discover their obscure meanings in the hungering human psyche. Painting and drawing per se mattered deeply to Brice, but not so much as what he painted or drew. Brice’s insistence on treading the perceptual ambiguity between representation and abstraction imbues his art with a profound yet lyrical aesthetic tension—a tension born of the incomprehensibility of what we, as viewers, most want to comprehend about human experience. Brice plumbs and probes the psychological depth of the very desire for “meaning” and “comprehension.” His target is as much the mind’s eye as the seeing eye, and pictures—icons, pictograms, portraits—always served as his conduit.

Brice’s foray into gestural, painterly abstraction was, then, a temporary—though bold and fruitful—venture, a successful experiment. But his interest in landscape and abstraction did not disrupt or displace his love of making figurative art. Many of his concurrent works from Brice’s “middle period,” roughly from the mid-1950s and well into the 1960s, were figure studies and moody meditations on the female nude, and they would become omnipresent in his oeuvre to the very end—but in a very different form. Clearly these nudes were of deep psychological importance to the artist, both an inspiration and a preoccupation, perhaps even a fixation. As early as 1953, in an unpublished note to himself from that year, while drawing images of nature on Mulholland Ridge, and reflecting specifically on the sounds of nature—“the crackle of the motion of the bug, the ant”—Brice concluded with an especially sensual, erotic afterthought: “There are so many other forms and movements thrilling to me, the sounds of thighs and shoulders, breasts, the articulation of hands and stance of legs and back. Soft billow—the pillow of warm flesh of the stomach, of the buttocks, of the pear and the peach—the clear waterof the mouth and of the apple.”4 Just as in this diaristic passage, his reflections on nature gave forth to an erotic reverie, so did the landscape elements of his earlier paintings and drawings yield to his passion for the female form.

The great majority of his pictures from this period were female nudes, with an occasional male nude making an appearance. They were usually contemplative, solitary figures in vague interiors or walking in a garden. These women are often shadowy presences—less like individuals with distinctly portrayed faces and a visible sense of character (though Brice occasionally did make some very striking portraits) than somewhat ghostly, phantom-like presences in isolation. Even when they appear with others, such as the nude male and female couple in a garden in the painting Two Figures (1965–66), they really are not paired at all, but are rather isolated from one another, each in their own space on opposite sides of the composition, separated pictorially by a tree trunk. The female resides close to the picture plane, while the male seems almost reclusive, deep in the recessed picture space. There is no clear situation, no identifiable characters, no discernable action in this tableau, yet the composition itself confers a poignant narrative full of longing.

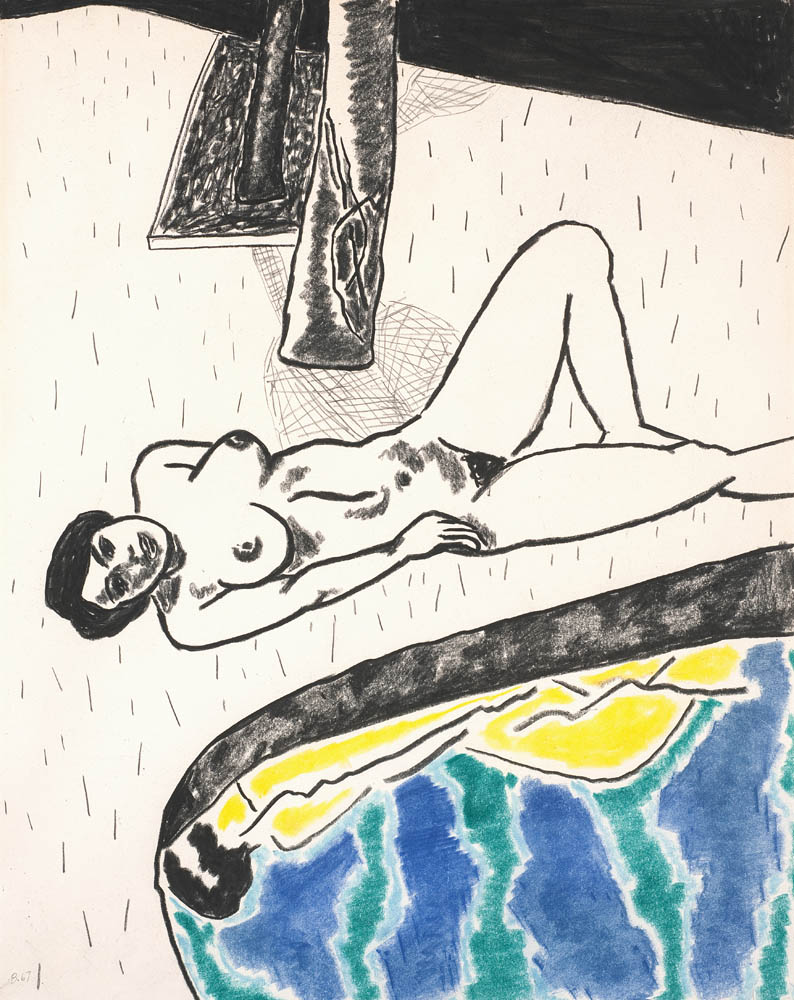

By the late 1960s, Brice, now nurturing a newfound interest in both early and late Matisse, began incorporating a brighter palette into his paintings and works on paper, and a flatter approach to modeling his figures. The pastel drawing Reclining Figure with Blue and Green Pond (1967) reveals a summary sense of depiction, a shallow, compressed pictorial space, and an abbreviated interest in detail. By now, Brice’s formal approach to making pictures was changing. They were becoming flatter, more frontal, and highly structured—almost as if an invisible geometry were governing the composition, independent of what it depicted. Though his devotion to the female nude remained the basis of his art, Brice began to grant himself license to render more abstractly. Some of the images began to look like the markings of a prehistoric cave painting,