The notion of a “trajectory” or “evolutionary arc” to describe an artist’s aesthetic development is a fond conceit held by art historians, critics and curators who constitutionally attempt, as their professional responsibility, to discern an orderly narrative to account for individual artists and collective historical movements. This presumes—or at least desires—that an artist’s development can be described as a progression of stages and phases, which culminates, finally, in a “breakthrough” mature or signature style. This commonplace schematic even allows for occasional fallow periods and epiphanies, recognizing that artistic genius is, after all, a human attribute and prone to the same distractions of attention and motivation that “ordinary” people must cope with.

In one mode or another, the female nude is the dominant subject throughout, increasingly abstract and increasingly sexualized, but always birthed by the womanly form, the female figure. What does it mean to have hewed with a career-long fidelity to the figurative tradition—especially, starting at a time when abstract gestural painting was supremely ascendant? As Richard Armstrong commented in his exceptionally thoughtful catalogue essay for the 1986 paintings and drawings survey organized by Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art and sponsored by the Fellows of Contemporary Art, “A gregarious man by nature, Brice is a loner as an artist. Though he joined the art faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1953, quickly becoming one of its most popular and respected members, the 1950s remained a period of relative isolation for him as he pursued an out of fashion, solitary aesthetic based on direct observation of nature.”9 It is safe to say that the same isolation prevailed after abstract expressionism was succeeded in turn by pop art, minimalism, conceptual art and all the other artistic advents in the international free-for-all that constitutes contemporary art in the 21st century, all of which Brice observed directly.

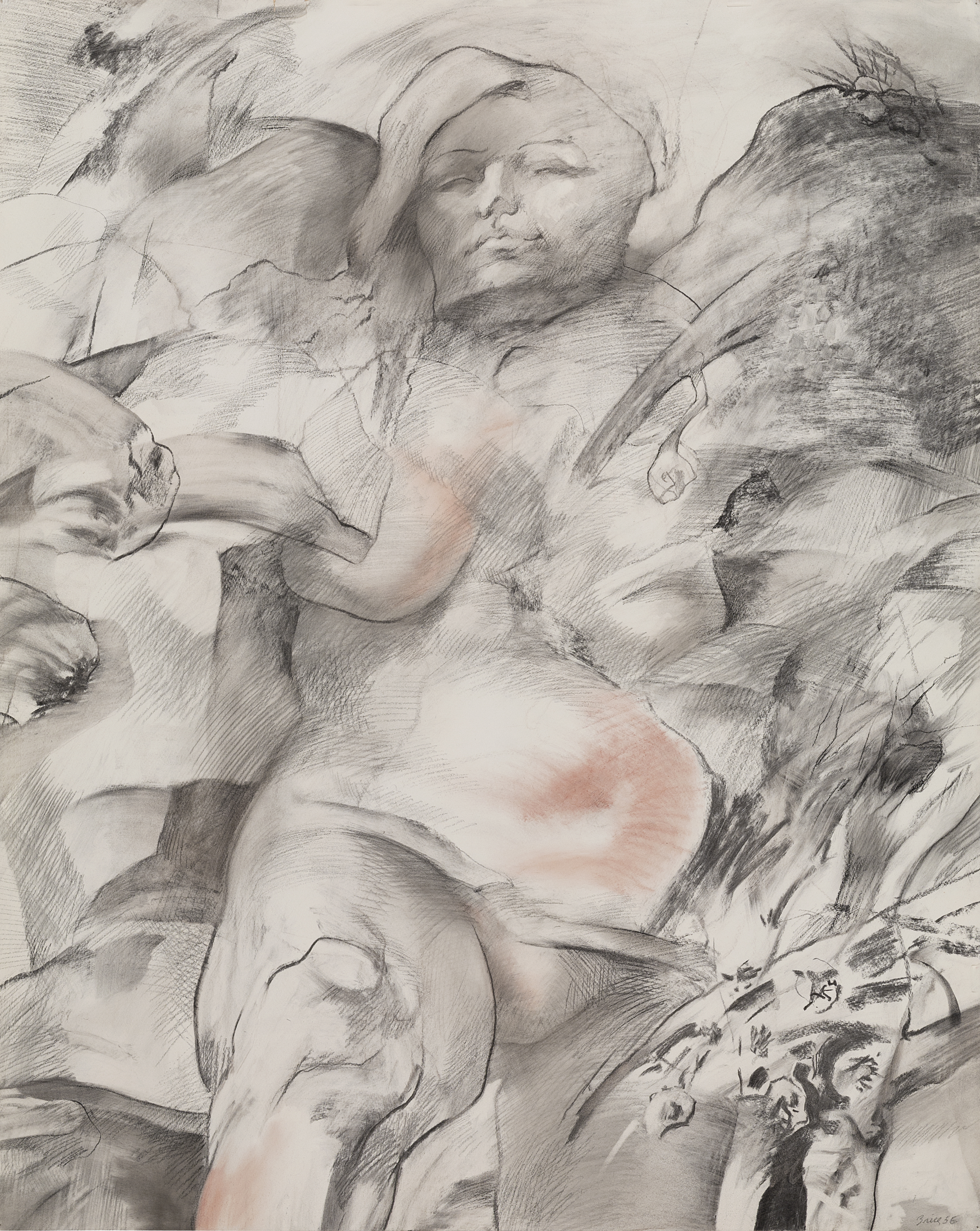

Woman and Land, 1956

charcoal and sanguine chalk on paperboard

40 1/16 x 32 in.

Collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966,

Accession Number: 66.617

Figuration, venerable as it always was and will be, must have seemed to many to be anything but avant-garde—indeed archaic—when Brice embarked down that road; and Brice’s beloved classicism must have impressed some as being not merely anachronistic but positively archaeological. Surely, his fidelity was not merely to an out-of-date mode as it was to his principles and personal aesthetic. But, rather than being a simple holdout for the values or the past, or a committed contrarian to the present, he might be well understood as a forerunner of a later, soon-to-be-described-as “post-Modern” sensibility—an activist in the name of artistic independence, not so much from the past as from the hegemony of current practice. Though he experimented, he resisted the dictates and the shibboleths of the present. Brice, who had a demonstrably sophisticated understanding of abstract expressionism and later currents of art practice, plainly did not want to be dragooned by prevailing artistic ideology as he developed his own ideas. Brice most assuredly did not absent himself from art history, past or present; he engaged it. Far from holding out against something, he was staking out to embrace something quite different and independent. His stance was a kind of precursor or a presage of what would later come to characterize the determined independence of most artists working today. But in pursuit of his intensely personal vision, and impelled by deep-rooted psychological realities that haunted his inner life, he worked in professional solitude to create an autographic body of work.

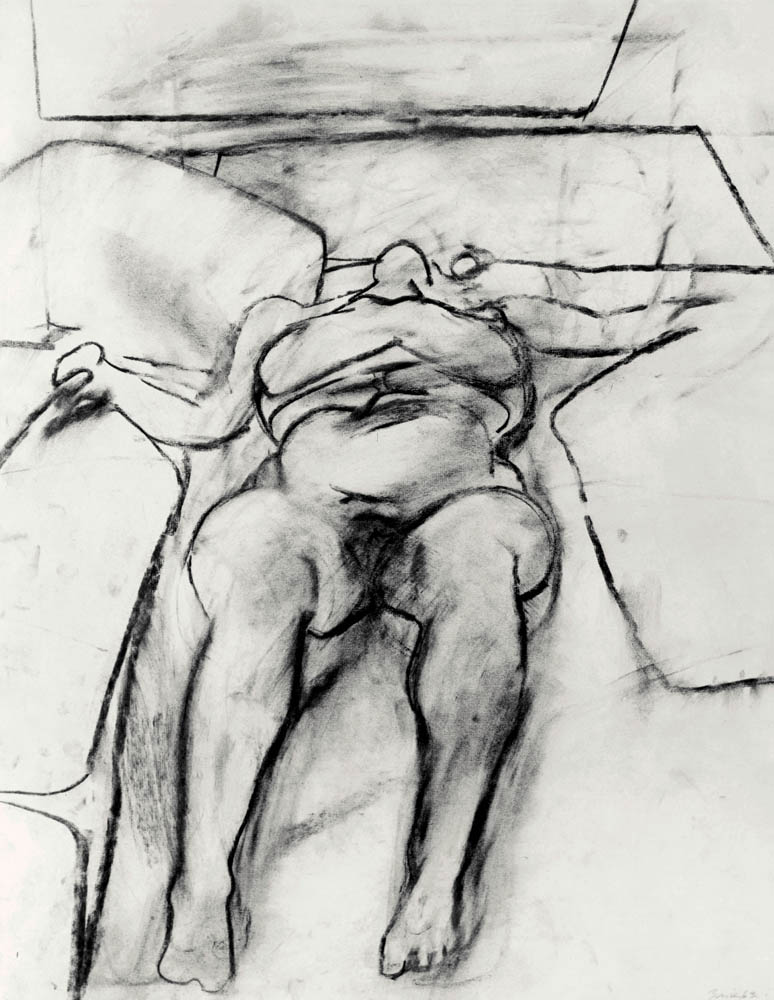

Large Figure, 1963

charcoal on paper, sheet: 25 x 18 in.

Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art

Purchase 65.38

It is not just an artist’s inner spirit that may inspire and shape creativity; spirit of place may sharply inflect it as well. John Brice has often remarked on his father’s love of California; and in William Brice’s pre-Greek art, the landscape elements that appear frequently are images inspired by the Southern California land, from the stones and rocks to the sea to the foliage and the trees—especially the eucalyptus trees that still thrive just outside his home. Clearly, Brice was artistically influenced by and felt aesthetically “at home” in Los Angeles. But it is worth speculating on his professional choice early on to stake his artistic career in Los Angeles, at such a remove from New York, the perceived epicenter of the international art world at the time. Had he gone to New York in the 1950s, as was de rigueur for so many aspiring young artists, it is probable—likely, in fact—that following his early incursion into abstract painting, Brice would have been encouraged by peers, dealers, collectors and interested critics to do more of it and with it—to develop his engagement with abstraction all the more. And, had he become an abstractionist in New York and subsequently attempted to return to representational figuration, as he did do in Los Angeles, it is just as likely that he’d have been derided as atavistic and retrogressive by those who earlier would have applauded his abstraction. He’d probably have gotten kicked around until it hurt sorely; or so we can speculate. In any case, Brice, for reasons we cannot know—and which perhaps he himself did not know—chose not to make art in New York.

Los Angeles artists at that same time did not benefit from a highly developed art critical milieu, nor did they suffer from the hyperventilation of art ideologues. A pronounced critical latitude pervaded the Los Angeles art scene during that period, and far from being factionalized and fractious, the artistic community—as has been noted in many accounts by contemporaneous artists, observers and art historians—it was animated by a spirit of open-minded interest and mutual supportiveness among its denizens.