Between Stability and Chaos: Part Five (of 6)—Brice Strikes Out

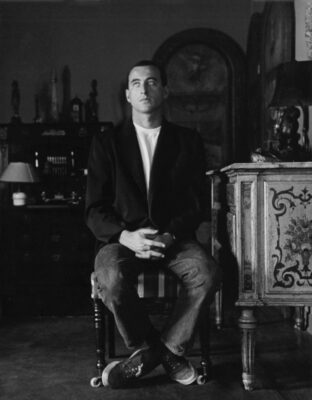

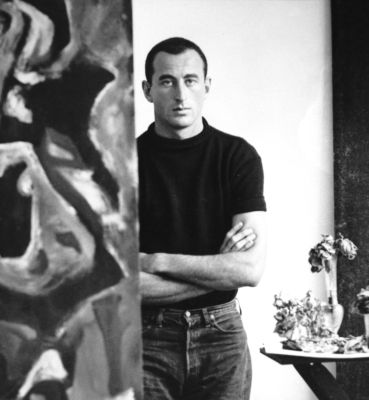

The formerly quiet, observant boy, who lived in his head, had not only become muscled up in LA, but at 18 he suddenly began to mature—and to develop an inner drive that would become as intense as his mother’s. But was it pushing him toward a bright future—or away from a haunted past? Either way, he moved.

In the remarkable ten years between 1939 and 1949, both Brice and the world faced an all-consuming surge of fantastic events that were challenging, frightening, but also exhilarating:

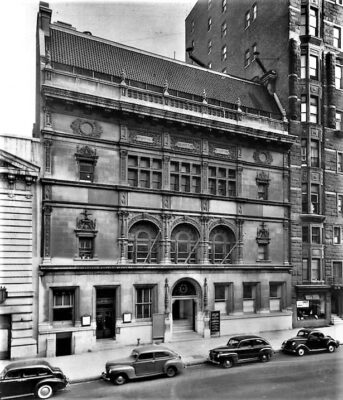

Within that short period, Brice struck out into the world. He raced from—Attending the Art Students League of New York, which has been significant in shaping America’s development in the fine arts, and so Brice joined the ranks of artists that include his mentor, Henry Boktin, Alexander Calder, Helen Frankenthaler, Georgia O’Keeffe, Barnett Newman, Man Ray, Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Louise Nevelson, Donald Judd, Roy Lichtenstein, Mark Rothko, Cy Twombly, Frank Stella, and, more recently, Ai Weiwei, becoming a bomb factory inspector at the beginning of WWII, volunteering for the Army Air Corps, marrying Shirley Bardeen (a marriage that lasted 66 years until Brice’s death), surviving WWII, attending Los Angeles’ Chouinard Art Institute while taking classes at LA’s Otis Art Institute,

briefly working for MGM studios creating ersatz Cézanne’s and Rembrandts for the movie sets, entering local and national art competitions and winning prizes, devoting himself exclusively to developing his art over 3 years, becoming a teacher at the Jepson Art Institute in Los Angeles—to attaining his first solo museum exhibition, at 27 (Santa Barbara Art Museum) and at 28 having his first one-person, commercial exhibition at New York’s pioneering Downtown Gallery. The gallery was the vanguard of American art and its gallerist, Edith Halpert, has been called the art-world tastemaker who effectively defined American art in the 20th century.

Brice’s Laudatory Reviews of his One-Person, Downtown Gallery Show:

Auspicious and indicative are the words that define the current exhibition at the Downtown Gallery of William Brice, 28-year-old painter-son of Fanny Brice whose canvases belie his age…Brice’s paintings have an inventiveness and maturity that make it difficult to believe that one so young could have come so far…To this reviewer, Brice’s work indicates a new and healthy direction in modern American Painting.

Marynell Sharp,

The Art Digest,

The News Magazine of Art,

February 15, 1949

…William Brice at the Downtown gallery has one of the most interesting shows to be seen…

Emily Genauer,

New York Herald Tribune,

Sunday, February 20, 1949

By 1949, Brice had struck out on his own, successfully. He had acquired a prominent New York gallery and the kind of recognition that allows a young artist to set his budding career anywhere he decides. New York, which had supplanted Paris as the world’s center of art post-WWll, was the obvious choice. Ambitious and aspiring artists from the 1940s onwards dreamed of heading to New York to make their careers, despite not having any contacts or money.

Besides recognition, Brice was a Manhattan native with many friends and important contacts, which included his mentor, Botkin. His mother maintained an array of extremely notable friends in all the arts in Manhattan and internationally. Naturally, Brice would move back to New York.

Except he didn’t. Neither did he go to Europe, to Paris where he spoke the language fluently. Instead, he made the then-unusual decision to remain in Los Angeles, which was still a cultural wasteland. Why did he choose to do this?

Brice had at least four strong motives for staying in Los Angeles:

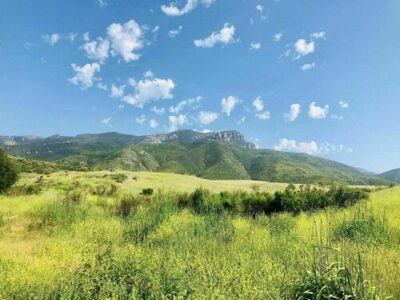

NATURE

Los Angeles’ surrounding wild mountain and ocean landscapes, and its special light and space, were especially important to Brice, personally and artistically, as his words below attest:

Born and raised in the city, how is it that I feel such joy that the turned soil is rich and soft under my feet and that the dry grass is toppled, strewn in marvelous disarray. My heart beats faster and I am exhilarated by the slightest shimmering of the silver-green leaves as a gentle gust caresses them. There is the new and spindly bush seeded by the side of the concrete road. Why, in how and where I grew, do I feel I belong to that little patch of green?

It is when I am high in the dry clean air watching the tenacity of the growth on the eroded hillside that I am at home, untroubled, excited, and alive…

William Brice,

Thoughts While Drawing at Mulholland Ridge,

1953

Whether as subject or element, nature became a significant, reoccurring theme throughout Brice’s oeuvre.

3 FREEDOMS

Freedom to Develop His Art:

In the mid to late forties and early 1950s, Abstract Expressionism was ‘the thing’ in the US, especially in New York, which Brice’s quote below addresses:

[U]ntil the second war—all artists went to Europe to study…Abstract Expressionism changed all that and it occurred at a time, let us say, that the whole self-image of America was one of leadership…So, it participated in that aspect that we were also cultural leaders.

…[Abstract Expressionism] was a marvelous, and is a marvelous moment, I think in the history of American painting. It was at the same time so exciting and so exclusive that it was a tyrannical moment…because if you didn’t do that, you didn’t exist.

William Brice,

Mid-Career, MOCA Retrospective Walkthrough Tour (YouTube)

1986

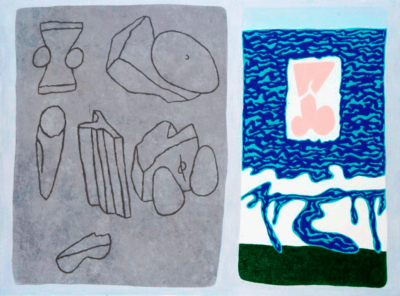

But Brice and his art did “exist”. He, and it, needed freedom from the strictures of art orthodoxy to develop. While he was extremely knowledgeable of art movements throughout history, Brice was determined to search for and to discover his own path in art.

Importantly, Brice’s work was specific in its imagery but was never literal. His practice was profoundly inquisitive and philosophical at its core. Brice’s inquiries are the actual subjects and themes of his work.

As Tony Berlant, former student, artist, and friend observed:

…Dick [Diebenkorn] was like Bill [Brice] in not wanting to be ‘on the scene’. That’s one thing that they shared. Bill maybe also had this sense that you give up a kind of freedom when you become part of the crowd. If you don’t take your place within the crowd, within the other group of artists, you’re able to be really independent.

Freedom From Disturbing Memories:

Throughout his life, Brice periodically visited Manhattan, always eager to feel its energy again, to walk and walk, to see shows at its great museums and galleries, to attend plays, and to enjoy so many old and dear friends. But two weeks were enough. The city’s jammed streets and towering skyscrapers and its tight compression uncomfortably mirrored Brice’s jumble of painful, haunting childhood memories. New York did not feel stable and was not a place he could call home.

Freedom to Maintain a Stable and Happy Family:

Brice wanted a family even though he had been effectively deserted by a father at birth and by a mother who could not ‘mother’ him. Perhaps his desire to have his own family was influenced by his experience of living with his mentor, Harry Botkin, and his family when Brice attended the Arts Students League. By all accounts, Botkin was a wonderful father and his family was extremely loving and supportive. Or, maybe it was simply to find the stability and warmth that had been so painfully absent from his life.

Whatever his reasons were, by early in 1950, Brice’s wife, Shirley, was expecting—and Brice was thrilled. He was determined to be an engaged, caring father—the opposite to his father, Nicky Arnstein.

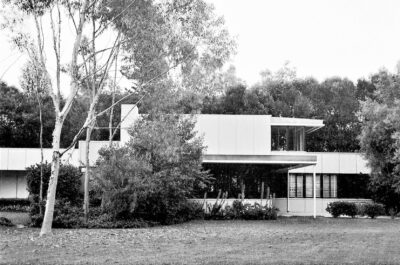

With a baby on the way, Fanny purchased a Richard Neutra-designed, mid-century, home for her son and daughter-in-law, located in Brentwood, West Los Angeles – The Richard Neutra Demonstration Plywood House, built in 1936.

From all appearances, life had become very good for Brice, and, most importantly, stable. But of course, everyone knows what they say about appearances.

* * *

To be Continued – See our Next Blog: Between Stability and Chaos: Part Six (of 6)—”He Can Run, but He can’t Hide.”