Between Stability and Chaos—Part Six (of 6): “He Can Run, But He Can’t Hide” – Demons are Forever

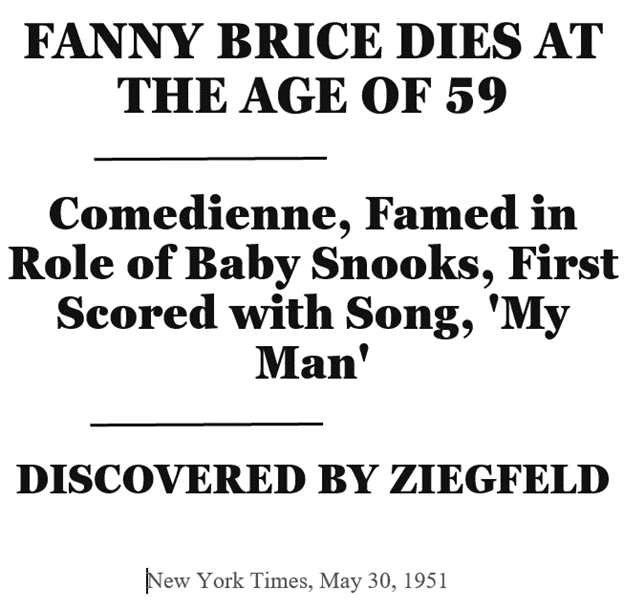

Two days after suffering a massive stroke that put her in a coma, William Brice’s mother died.

On the day of Fanny Brice’s funeral, Brice and his wife’s car wove through a crowd of over 1,300 fans jamming both sides of Hollywood Boulevard in front of Temple Israel, waiting to bid his mother goodbye.

Inside the Temple, Brice sat among the crowd of mourners, next to his wife, sister, and movie agent brother-in-law, surrounded by the city’s high and mighty, including legendary, powerful studio heads like Louis B Mayer, super agents like William Morris’

Abe Lastfogel, Fanny’s agent, and many of Hollywood’s fabled stars and comedians. Over a hundred grand floral pieces filled the temple’s entire pulpit area. A colossal ring of orchids had been sent from Billy Rose, Fanny’s third husband. Her casket was shrouded by hundreds of carnations.

At barely 31 years old, Brice had suddenly lost the commanding figure in his life.

BRICE’S GHOSTS

Mother: As She Was Large in Life, so She Was in Death

For the rest of Brice’s life, his mother’s sizable public mystique, as well as his tangled memories of her, lived on.

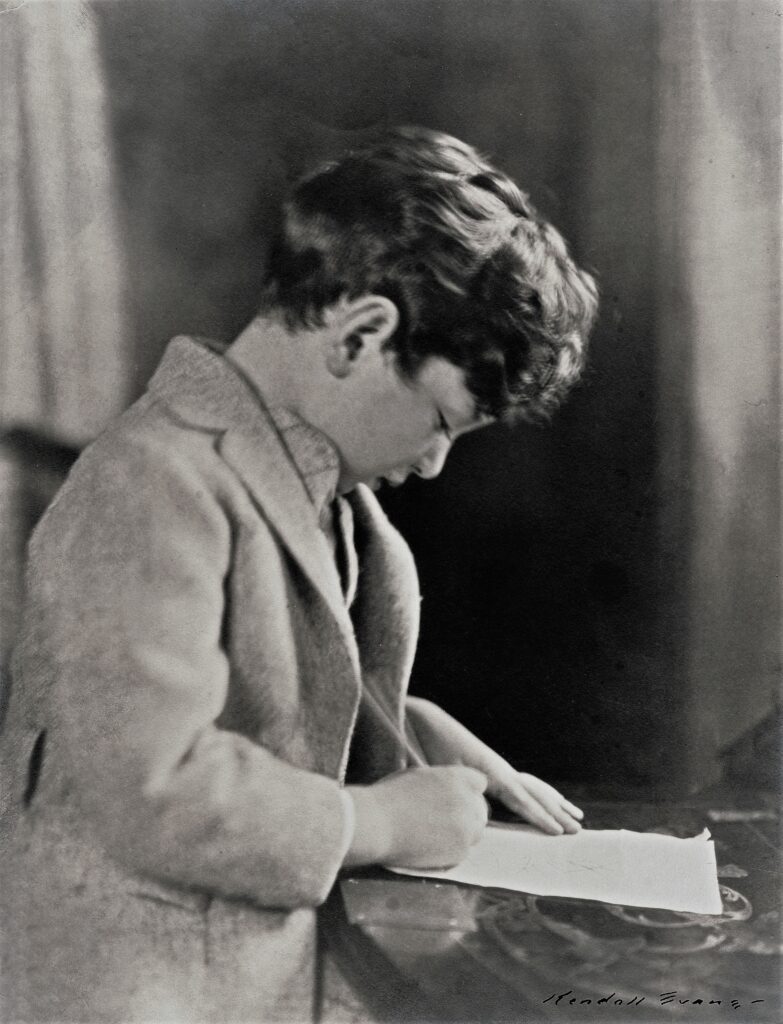

To a friend, Brice shared an anecdote about the morning when, as a teen, he was about to enter his Manhattan public school when he noticed a limousine pulling up across the street. It was his mother’s.

Its rear window rolled down as his mother’s hand eased out, her face unseen. She beckoned him with bended finger.

Thrilled, he rushed to her. Just as he neared, her limousine drove away as his mother rolled up her window, leaving Brice in the street, alone. As an adult, Brice would recount this small event with a laugh as if to say, ‘How about that for a mother!’

To another friend decades after his mother’s passing, Brice described her as “cold”.

At another time, though, Brice commented, “I didn’t really get to know her until we moved to Los Angeles when I was 16. She wasn’t so much a mother as my best friend. She was a fascinating person.”

Indeed, Fanny admired her son’s maturing intellect, his absolute dedication to his art, and so she became an advocate for his budding talent.

Father: Brice’s Specter

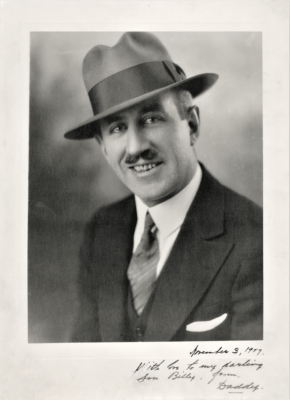

Nick came calling shortly after Fanny’s death. As uncomfortable as it was for Brice to see his father suddenly standing at his front door after 24 years of abandonment, it was particularly unsettling to see his wife at his side—a wealthy Pasadena socialite. Nick introduced her, “Meet your new mother.” “New mother?” Brice was shocked by his father’s remarkable insensitivity. Later in life, Brice occasionally recounted this incident, too, and with a similar tone of ironic amusement.

A few years later, Nick invited Brice down to San Pedro Harbor for a tour of his new business project: a “banana boat”/cargo ship that he was converting into a swank, gambling casino. After completion, the ship would be anchored a mile offshore and beyond the legal limit against gambling.

Arriving at the dock, Brice exited his car to be greeted by his father, dressed in perfectly polished two-tone shoes, flannel whites, a double-breasted, blue blazer with shiny brass buttons, and sporting a captain’s cap with scrambled egg on the visor.

Brice trailed his father as they made their way through the bowels of the ship while Nick ‘expertly’ informed about the ongoing work. Passing beneath workmen perched on catwalks and ladders, welding, hammering, and painting, Brice couldn’t help noticing the men’s disgusted expression as his father passed below them, dressed to the nines.

As father and son said their goodbyes, Nick pitched his new business opportunity: “This ship is gonna be the cat’s meow; it’s gonna be worth millions. We’re nearly there! I’m just thirty thou short; just thirty thou. I don’t suppose you could help me a little bit, just a little bit, Billy? Pay you right back plus interest as soon as the dough starts rolling in. Ground floor; gonna be worth millions!”

Brice was unequivocal: “No,” and drove away.

Brice saw his father one more time, briefly, before Nick died, alone, in 1965.

Mentor: Botkin’s Spirit

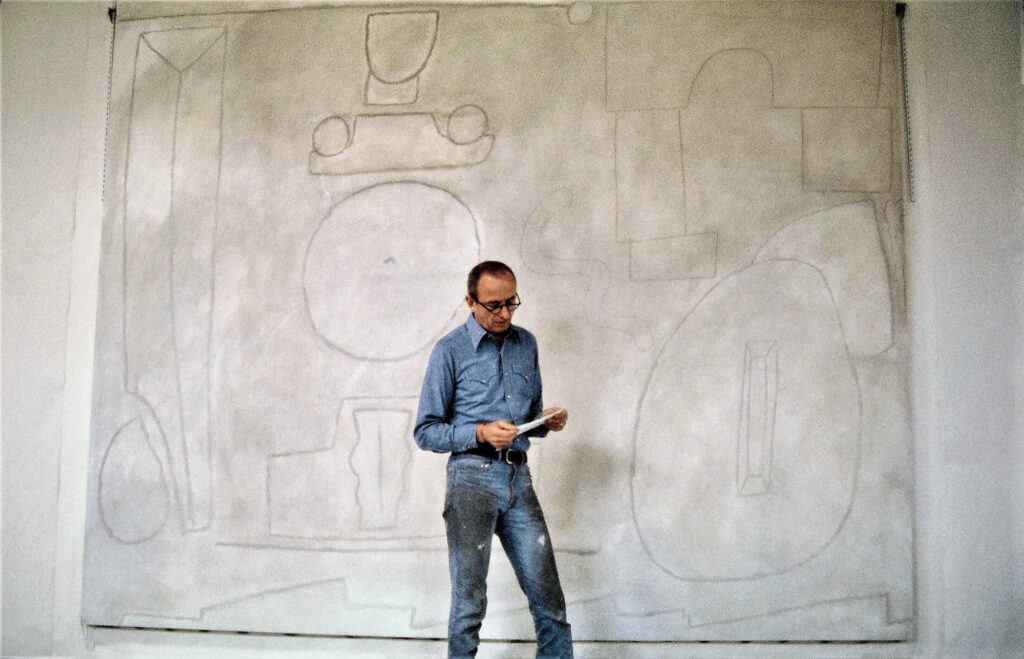

Brice’s year and a half spent with Botkin as a young teen laid the foundation for the rest of Brice’s life. “By the time I was 16, I knew [art] was to be my life. And I’ve never changed my mind,” related Brice to a gathered crowd during his 1986 MOCA mid-career retrospective walkthrough.

Following high school, Brice decided to return to New York to attend the Arts Students League, Henry Botkin’s alma mater and where so many renowned American artists had studied. During this time, Brice stayed with Botkin.

Brice claimed that what he learned living with Botkin, his wife, and their two children, that year was not about art, but about the life of an artist. This was significant to Brice. So was his daily experience of being part of a ‘normal’, happy family and witnessing Botkin as a loving, engaged father.

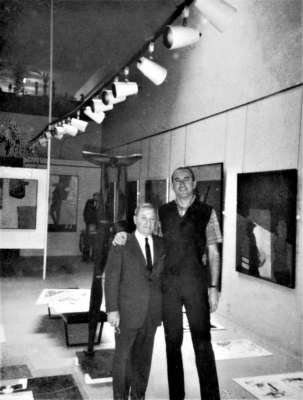

What precisely did Botkin mean to Brice, to his art, and to his life? We know from Brice’s letter of condolence to Botkin’s children upon Botkin’s passing in 1983.

The letter is remarkable for two reasons. It reveals Brice’s deep reverence for Botkin. It also reveals uncanny similarities between the two men and artists when one compares what Brice wrote about Botkin to what Brice’s students have said about him as quoted below in parallel to Brice’s letter:

Brice on Botkin –

Condolence Letter to His Children

Brice Students on Brice –

Quotes

Harry, so long now dear to me, when I was fourteen opened to me a view of passionate engagement in the practice of art. Tough-minded and discerning, he was enthusiastically appreciative, capable of being deeply moved by the wonder of it—art. He was totally absorbed in it and conveyed to me through his gentle teachings and infinite patience and through his own creative process a value in life commitment. In his subtle and resolute persistence and his integrity of conviction and sensibility, he was confident of his own powers as an artist but remained ceaselessly open and questioning, never complacent and never arrogant. Even in the late years of his life, he retained an adventurous excitement and youthful vibrancy, an encompassing generosity. Harry did not know how dear he is to me and nor did Rhoda. I say it now to share with you Antoinette and Glenn, and with those he loved and those who loved him, the gratitude for all that in the sharing of his life with us he illuminated. To the degree that we actually do live within one another, there is experienced an immortality.

He instilled in us a love of art history. He had enthusiasm. He’d get us hepped up.

His lifetime of devotion to his work, even in the face of obstacles, has been the most powerful teaching of all. …he never had any sense of superiority.

He was certainly a model for intense commitment as an artist…

…He actually had a loving way, a gentle way about him.

What becomes unassailable is that Botkin was not so much Brice’s mentor as his de facto father.

Botkin’s choices to be a caring and honorable man, to be devoted to something bigger than himself, to be a maker, and to be a giver, were in stark contrast to Julius Nicky Arnstein’s choices to be devoted only to himself—to con, to philander, to steal, to be a taker. For Brice, Botkin was an oasis in his desert, and he couldn’t stop drinking from it for the rest of his life.

AN INHERITANCE OF CONFUSION

These three antithetical, forceful personalities remained active in Brice’s psyche, ever threatening to pull him apart.

His father’s choices and behavior marked and disgusted Brice. Nonetheless, for the rest of his life, Brice secretly feared that he might become his father: that he might have his father’s ‘blood flowing through his veins’. Would his awareness of his father’s character be enough of a ‘blood-brain-membrane’ to protect him from his father’s character pathogens, or would they somehow seep through to Brice? Nick’s late intrusion into his son’s life amplified Brice’s foreboding about who he might yet become.

Botkin remained Brice’s North Star for the rest of Brice’s life. It was Brice’s experiences with Botkin that drove Brice to become both an artist and a teacher, who helped others develop their talent and their personal growth. As Brice has been quoted, “I was fortunate by personal inclination to find teaching appropriate for me…It was a way for me to do something that I really believe in very strongly, which has to do with participating in the continuity of art, the ongoing-ness or art. I felt very much connected, indebted to the persons who had taught me. When I looked at the work of artists, it was as if they were alive again, with me. And so, that sense of continuity was significant to me.”

From his mother, Brice inherited laudable values and traits, many that Botkin also shared: a strong set of ethics, a relentless creative impulse, an interest in people, a desire to help others, intelligence, inquisitiveness, elegance, a deep sense of irony, juxtaposition, and humor.

However, Fanny’s contradictory facets of “mother” and her complex, uncompromising personality, one bereft of warmth, left Brice with painful enigmas about who she was and what kind of mother/son relationship they had. Moreover, memories of his harsh governesses, proxies for ‘mother’, also cast long shadows over his life.

Unfortunately, Fanny’s early death ended any chance that mother and son could truly become reconciled. She would not see Brice come into his own as a man with his own ‘power’. Never would he receive her due regard for him as a person in his own right.

But what if his mother had lived another fifteen years until she reached seventy-five—what would she have seen? How might their relationship have changed?

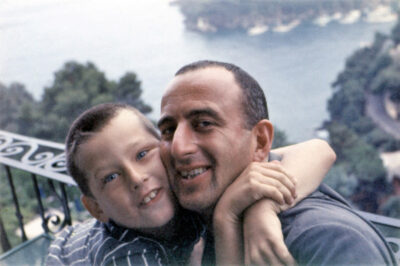

She would have experienced her son as an engaged father—a ‘parenting style’ so unlike her own, but so similar to his mentor’s parenting and of his mentorship of Brice. She would have seen Brice and his son’s positive, intimate, loving relationship. What would she have thought of her son, the parent?

She would have also seen her son become a revered and sought-after UCLA professor of art, who helped lead its art department to national and international recognition, a man so very different than his fraudster father.

And she would have seen her son’s works collected by America’s most prestigious museums as well as his representation by important gallerists who also showed artists such as Francis Bacon, Louise Bourgeois, Georges Braque, Alexander Calder, Richard Diebenkorn, Mark di Suvero, Helen Frankenthaler, Alberto Giacometti, Joe Goode, David Hockney, Edward and Nancy Kienholz, R. B. Kitaj, Gustav Klimt, Lee Krasner, Gaston Lachaise, Henri Matisse, Joan Miro, Henry Moore, Ed Moses, Alice Neel, Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Pablo Picasso, Ken Price, Man Ray, Egon Schiele, Cy Twombly, and Peter Voulkos amongst others.

But his mother died too soon. Never would the power dynamic between Brice and his formidable mother become leavened.

HE CAN RUN, BUT HE CAN’T HIDE – DEMONS ARE FOREVER

Despite Brice’s successes, the blessings of his birth, and no matter how he reached for his better angels, the effects of his parents’ personalities and his childhood abandonment became internalized. At his core, he experienced a black hole, a frightening void of inner emptiness that occasionally plunged him into despair, self-loathing, and intense confusion. At these times, he became dangerously desperate to fill this emptiness by any means possible.

No matter how hard Brice tried to outrun his demons, they periodically erupted from his depths to wreak havoc on his personal life and threaten his career.

Thus, Brice did not conquer his demons. Instead, he used them to gain vital insights, which became the wellspring of his teaching and of his art.

However, in his concluding years, Brice seemed to come to terms with them; to accept the paradoxes of his life.

In fact, his last works appear to move from a conflict of opposites towards a synthesis of dualities, and so into investigations of yet deeper truths.

What emerges when one compares Brice’s concluding works to his early ones is the picture of a significant and intriguing artistic journey, one that reflects Brice’s fascinating journey in life.