Brice and Diebenkorn—Divergent Paths to Discovery

Brice and Diebenkorn—Divergent Paths to Discovery

If you hang around artists for a while, you’ll probably hear words like “choices” or “possibilities”. What they’re talking about is the creative processes they use to solve “open-ended problems” and the range of choices they have before them in order to do so.

Each artist intrinsically engages in processes that are unique to their personality and distinct quest. Thus, each artist’s overall strategy, including how they choose to employ intuition and awareness, is evidenced in their work.

How?

For clarity, let’s start with the basics. The creative process attempts to invent a thing of value that does not yet exist. Typically, but not always, it begins in the artist’s, inventor’s, scientist’s, etc., subconscious, which he or she has been wrestling with to find the right solution to some creative/open-ended problem. If the process begins in the creator’s intuition, he or she may suddenly get a flash of a small idea. That is, the creator notices something that is attractive to him or her and begins to “play” with it.

In time, additional, related possibilities bubble up in the creator’s mind. He or she chooses the ones that seem to “fit”. The new choices attach to the first ones. Think of this as similar to how molecules attract and join with like-molecules. The quilt of each artist’s choices becomes jigsaw puzzle-like in that they begin to form an image of what each artist is after. So, what began as an unconscious process ends in full awareness of the solution to the open-ended problem. The creator’s intellect can then chime in to manifest the solution. All of this is reflected in their works.

However, sometimes intuition and awareness come in the reverse order, which is equally telling.

On Intuition:

The intuitive gift is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.

Albert Einstein

On Awareness:

To become different from what we are [to grow], we must have some awareness of what we are.

Eric Hoffer

On Intellect:

I throw a spear into the darkness. That is intuition. Then I must send an army into the darkness to find the spear. That is intellect.

Ingmar Bergman

Why is this Important to Viewers of Art?

Understanding how a given artist defines his or her choices and approaches to open-ended problem solving, offers vital keys to unlock the secrets of “what their art is about”. It’s a kind of “reverse engineering” understanding that informs not so much an artist’s subjects, but how the artist views them. If the view takes time to identify the choices made and other possibilities that were rejected, then the view can better understand and appreciate an artist’s work or his/her oeuvre.

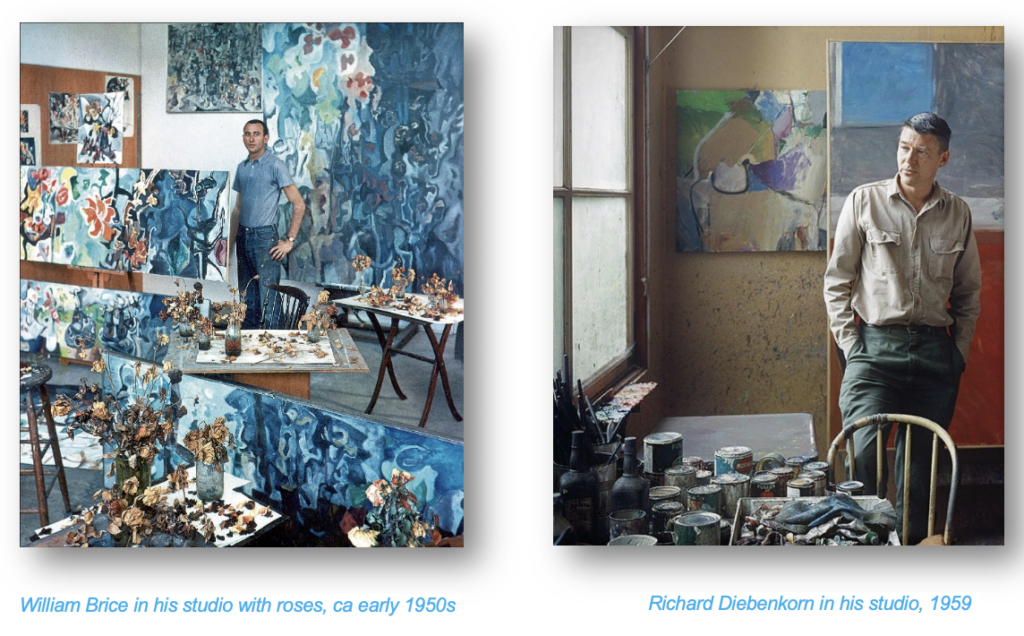

Let’s take Brice and Diebenkorn as Examples

Introduced to each other in 1953 by close Brice friend, gallerist, art collector and movie star, Vincent Price, Brice and Diebenkorn were naturals to became best of friends. They came from well-heeled families, spent at least their teens and most of their adult years in California, became passionate about art at an early age, engaged at times in figurative and landscape art, developed their own unique voices, taught at UCLA together, and even celebrated their birthdays together as they were born one day and one year apart.

But there were differences too, of course. The one that concerns this blog is how they uniquely approached “open-ended problem solving”.

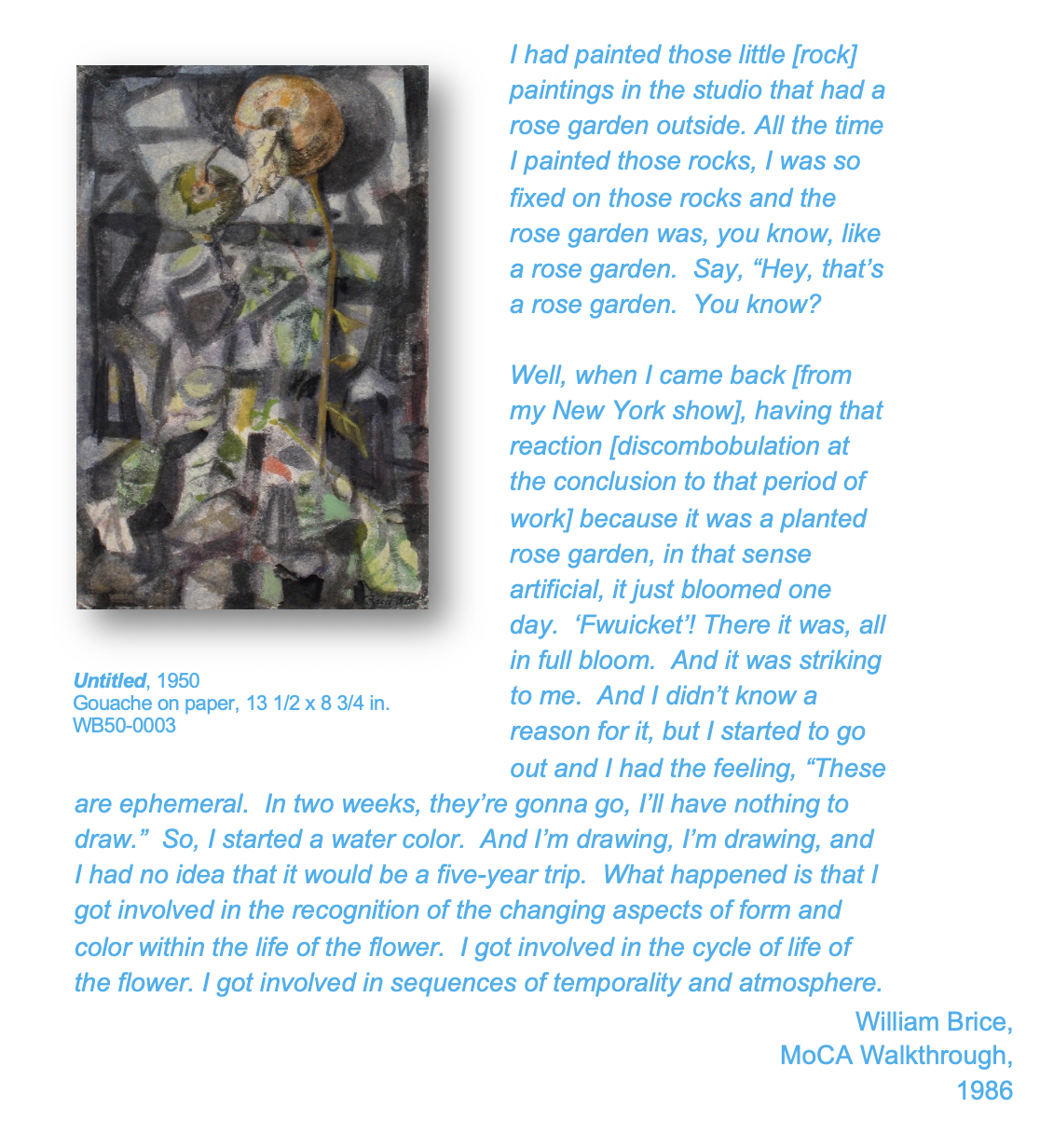

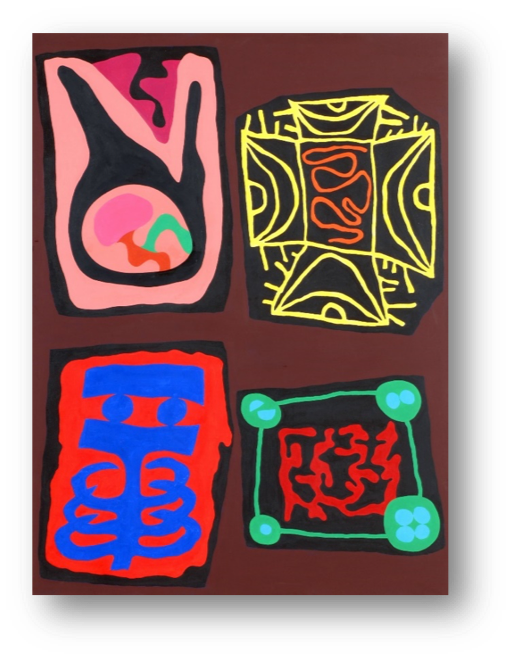

Brice

Intuition kicked off his process. Something, a small thing, would capture his attention. Without understanding why, he began to play with it, to put it at the center of his practice and inhabit it. He trusted that awareness would eventually follow and grow. As he continually assessed these works step by step, he found definition and insight—awareness—and became ever more conscious of the core of his attraction and its ramifications, and so of its meaning to him and its themes. His range of considerations expanded. Discoveries were made, and his feelings and ideas became ever more realized. This was so in his career’s specific turns and, ultimately, in his entire oeuvre.

Diebenkorn

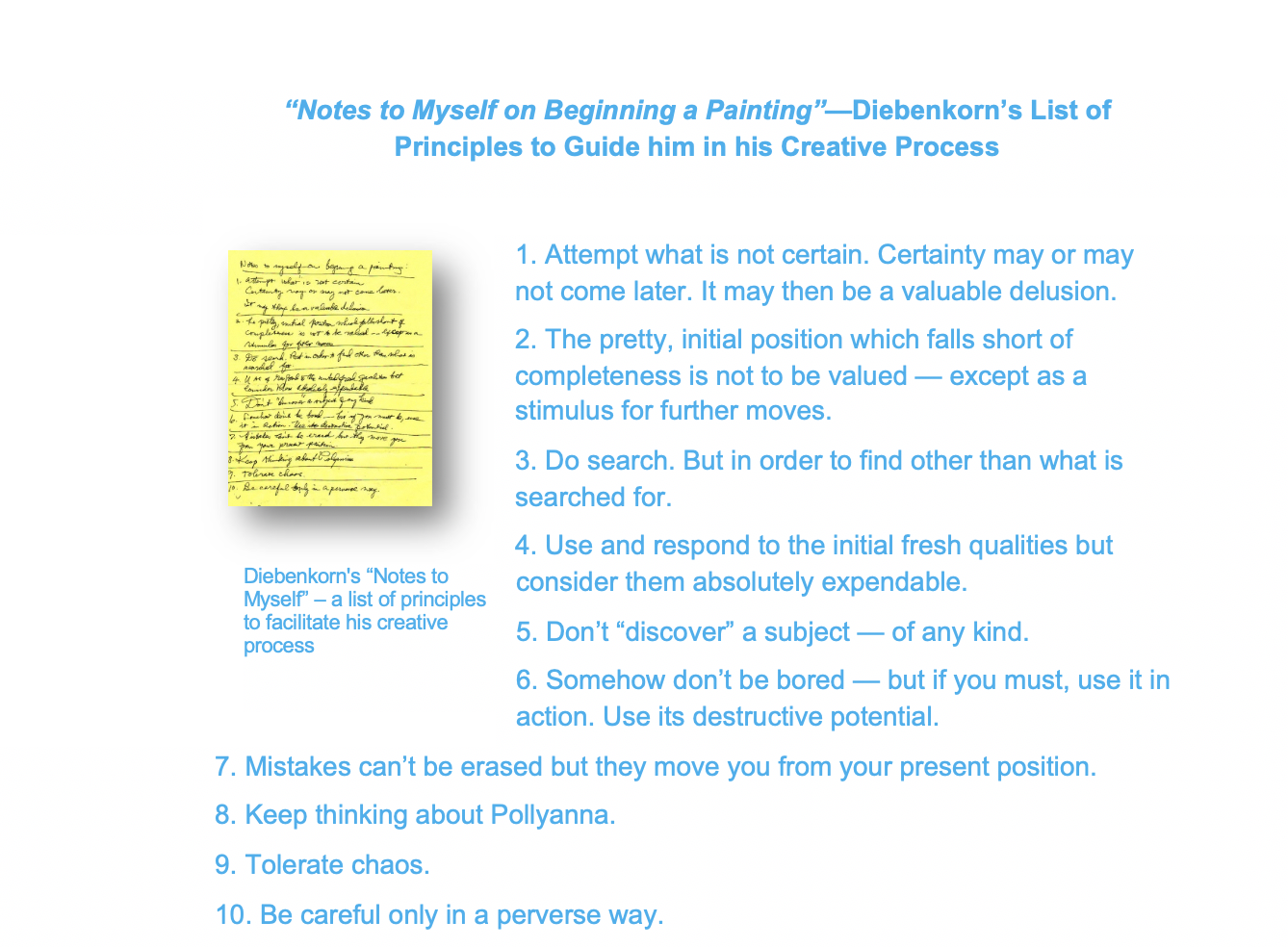

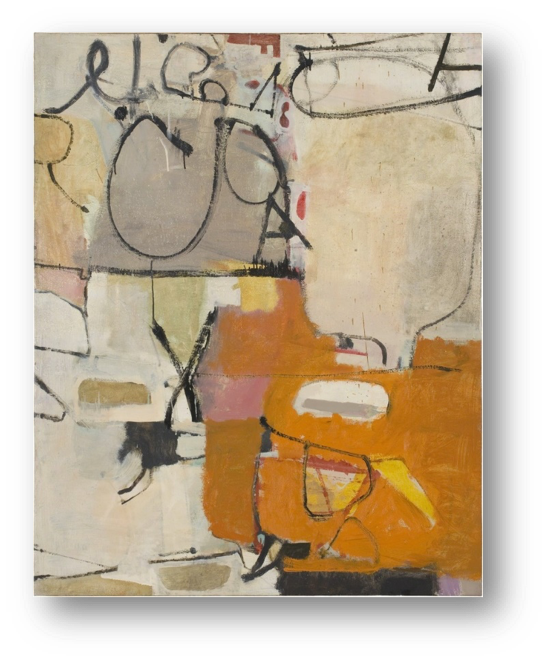

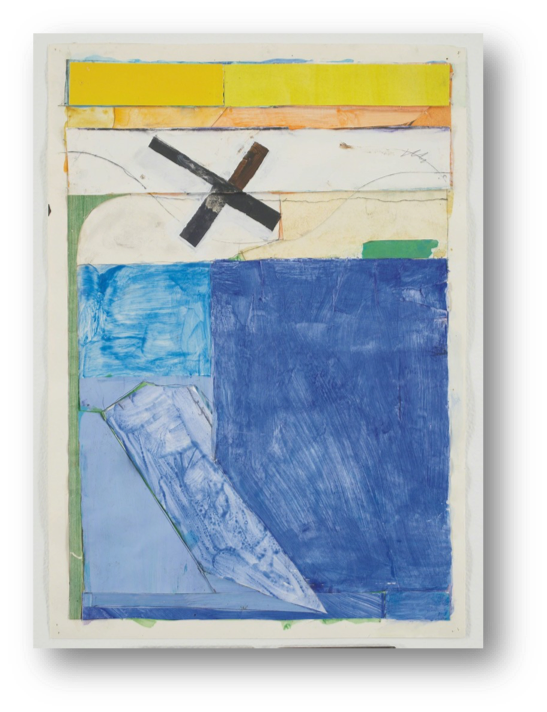

In contrast to Brice, Diebenkorn’s “Notes to Myself” below, which was found in his personal papers after his death, is a testimonial to his “open-ended problem solving” method. His began with awareness and intellect to frame and guide his creative departure point—so that his intuition could run free in a meditative state while he engaged in making art, which itself may be seen as meditations on nature and landscape, and so share his contemplative journey of discovery with the viewer.

Oeuvre

Brice

As his creative processes reflect, my father was able to look at and to discover the world ‘inside of him’: his feelings about time and relationships, about nature vs people, about matter vs. spirit, etc.

Even in the formal elements of his work Brice sought “a composite of values consisting of empathy, association, emotion, recollection.” This choice was a highly sophisticated one. It began with the mature and full consciousness of both his subject and his complex, deep knowledge of the visual language, which came together in the 1970s and 80s. Combining subject and form to achieve full articulation was particularly relevant to his art. For my father, form developed not as an attractive thing in itself, nor merely as a lattice to hang his considerations on, but as an equal and inherent part of his expression. Thus, viewer’s awareness of this choice alone may help them to more fully appreciate what they see in front to them. Such choices resulted in beautiful yet penetrating investigations into the human condition as he experienced it, ones that by the end of his life entered into the realm of the metaphysical and became transcendent.

Diebenkorn

Diebenkorn’s “Awareness/intellectual first, and then intuitive” process allowed him to immerse himself in that which was outside of him. His process facilitated engagement in his lifelong joy of “looking”, of contemplating the visual ‘music’ of his surrounding world—to imbibe his outward environment, both its exterior and interior spaces—while including his internal reactions to them. All the while, he’d rearrange a work’s elements in his mind and on his canvas according to his evolving responses as he looked. He elected to include his “mistake” choices, too. So, his works evidence his evolving responses—his process—in ghostly records of his looking and evolving reactions. Due in part to their inclusions, his work feels alive. The combined results are transmogrifications of his experiences in works that are also transcendent.

By understanding Brice’s and Diebenkorn’s distinct processes, the possibilities they considered and choices they made, and how they differently employed intuition and awareness, we can better appreciate and engage their art just as we can the art of others.